How to deliver user-centred healthcare design

‘The cure for the pain is in the pain.’

Rumi

Key to any healthcare intervention is understanding and addressing personal experience. In clinical practice this is done by taking a history, observing, testing, and examining. We manage, assess, and reassess.

The factors forming personal experience are always complex. It’s only once the ‘pain points’ within that complexity are understood that effective interventions can take place.

In technology-enabled healthcare, design-led approaches can be used in a similar way to clinical methods to understand user experience and solve complex problems, as well as considering how best to deliver solutions.

These approaches have a long history in business. Management consultants McKinsey found, for example, that companies with strong design practices increased their revenues at nearly twice the rate of industry counterparts (https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-design/our-insights/the-business-value-of-design, n.d.)

Today’s CCIO needs an understanding of these approaches to effect digital transformation.

What is User-Centred Design?

Human or user-centred design (UCD) is the creative philosophy and associated processes used to understand and address user needs, especially where problems are complex (Snowden, n.d.) (Norman, 2013).

In the ‘Design of Everyday Things’, Donald Norman describes how this complexity often manifests itself as difficulty defining the specification of a product or service.

UCD addresses this by deliberately avoiding specifying the problem at an early stage. Instead, UCD focuses on the iteration and rapid testing of ideas, allowing test results to quickly feed back into modifying the approach and the problem frame.

The design process allows us to ‘find the right problem to solve and to solve the problem the right way’. The result should be products and ‘services that achieve outcomes that solve problems for users’ (Vaananen, n.d.).

The double-diamond approach to innovation

‘Wherever there is decision there is design.’

(Grinyer, 2021)

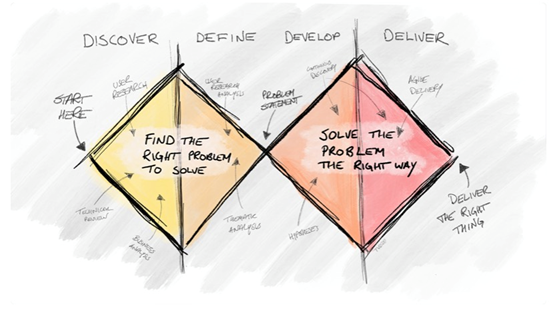

Figure 1: Version of UK Design Council’s Double Diamond diagram (https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/tools-frameworks/framework-for-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond/, n.d.) (Vaananen, n.d.)

Figure 1 depicts a version of the UK Design Council’s double diamond process model for innovation (https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/tools-frameworks/framework-for-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond/, n.d.).

It’s divided into four stages, although the process is not linear and there will often be a need to return to a stage as more is learned. It’s often necessary to reframe the problem to get the best solution.

These stages are:

Discover – understand the problem as completely as possible. This might include desk and user research, such as surveys, interviews, empathy mapping and observation (Muratovski, 2016). Observation can be ‘participatory’.

The best design is usually done in the place where it’s needed. If good user research isn’t done, assumptions about the problem can generate solutions that don’t meet user need (Nuckley, 2023).

Define – take a closer look at the challenge by analysing material from the discovery stage. Specific tools can include service interaction mapping and service blueprints (Grinyer, 2021).

Develop – Once the problem is more clearly defined, brainstorming and other divergent thinking methods can be applied. This is likely to lead to creative solutions, especially if a non-hierarchical approach is encouraged to deprioritise the loudest voices in the room.

Deliver – flexible prototyping and testing are central to delivery (Agile and government services, n.d.).

Other frameworks, tools, and processes

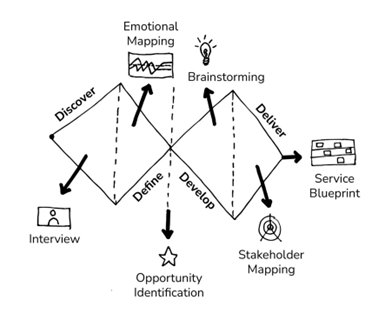

Figure 2 Examples of tools used within the design process

There are many other frameworks, tools, and processes within the discipline of ‘design thinking’ that can help explore challenges and generate solutions. The key is to select what’s appropriate for the type of problem being worked on. (Muratovski, Research for Designers, 2016).

Continuous or quality improvement, for example, sits under the design umbrella within the field of ‘action research’. It’s well suited to systems where there is a requirement for existing practitioners to “investigate and evaluate their own work’ (Muratovski, 2016) and where there’s considerable ambiguity around how to make improvements.

Further examples of frameworks, tools and processes are shown in figure 2.

What does UCD mean for CCIOs?

“I wish people would stop trying to sell me solutions for problems that I don’t have”

NHS CCIO

UCD means being able to deliver effective digital transformation

UCD is vital to delivering digital strategy, building team capability, and encouraging a culture of innovation. The CCIO is usually at the heart of this, often acting as the interpreter for multidisciplinary teams. Adopting a UCD approach means that there’s a tried and tested philosophy alongside effective tools and processes that a CCIO can employ in pursuit of effective digital transformation; whether that’s through clinical leadership for EPR implementation or evaluating the latest artificial intelligence tool.

UCD gives CCIOs ways to deal with complexity

In healthcare, the relationship between cause and effect is often not linear, e.g. implementation of an EPR and the impact on patient safety. Key features of UCD, such as user research and iterative methods are geared towards dealing with complexity (Snowden, n.d.).

UCD means being able to deliver concurrently

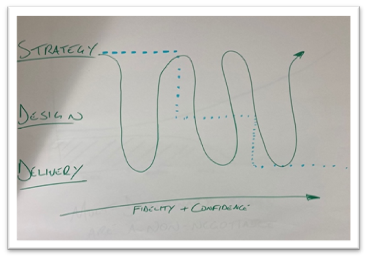

Figure 3 Concurrent Development Browne, 2023

Well-functioning modern digital teams in any industry need to be able to develop their strategy, design, and delivery concurrently, rather than in sequence (fig 3 (Browne, 2023).

Adopting a UCD approach allows CCIOs to move away from continuous pilots towards working practices that are more likely to uncover bias and generate truly new ways of working (for example, see Royal Free London’s approach to intelligent automation – (Ali, n.d.)).

How can CCIOs implement UCD?

Bring the user in

Implementation of UCD can begin simply with a commitment to making steps to bring in the user. For example, by ensuring completeness of stakeholder mapping and conducting interviews with users early in the design process.

Increase design capability

Design capability can be increased internally through education and recruitment of professional designers, as well as exploring engagement with external design specialists.

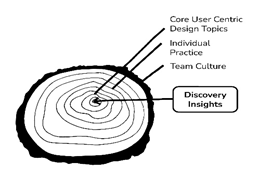

In user-centred work we did in NHS England, for example, our discoveries informed an education programme aimed at building design capability in one team. Through surveys and interviews we established a curriculum that would increase the user-centredness of our work via individual practice and team culture (figure 4.)

By adopting similar practices, CCIOs can discover how best to implement UCD in their own healthcare organisations.

Figure 4 Design Capability in the Digital Care Models Team, NHS Transformation Directorate 2022

Credits for figure 2 & 4 to Helena Traill , Healthcare Designer

Thanks to Tero Vaananen , Tony Browne and Pete Nuckley for their help with the preparation of this article

Works Cited

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://medium.com/wardleymaps .

(n.d.).

Agile and government services. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/service-manual/agile-delivery/agile-government-services-introduction

Ali, L. (n.d.). Retrieved from Innovation Collaborative Blog: https://gbr01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffuture.nhs.uk%2FInnovationCollaborative%2FmessageShowThread%3Fthreadid%3D10678606&data=05%7C01%7Clia.ali%40nhs.net%7C69c103ec10d34b6fd40c08db2a2e6deb%7C37c354b285b047f5b22207b48d774ee3%7C0%

Browne, T. (2023). Digital Transformation – personal communication.

Grinyer, C. (2021, October). Lecture on Service Design. MSc Healthcare and Design, Royal College of Art.

HBR. (n.d.). Close the gap between designing and delivering a strategy that works. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/sponsored/2017/10/close-the-gap-between-designing-and-delivering-a-strategy-that-works

Holmes, K. (2020). Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. Cambridge MA.

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-design/our-insights/the-business-value-of-design. (n.d.).

Loosemore, T. (2017). Retrieved from https://public.digital/definition-of-digital

Muratovski, G. (2016). Research for Designers. SAGE.

Muratovski, G. (2016). Research for Designers. Los Angeles: Sage.

Norman, D. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Orton, K. (2017). The Sweet Spot for Innovation. Retrieved from https://medium.com/innovation-sweet-spot/desirability-feasibility-viability-the-sweet-spot-for-innovation-d7946de2183c

Smith, R. (2021). Retrieved from Making content about skin symptoms more inclusive: https://digital.nhs.uk/people/nhs-digital/blog-authors/rhiannon-smith

Snowden, D. (n.d.). The Cynefin Framework. Retrieved from https://thecynefin.co/about-us/about-cynefin-framework/

Vaananen, T. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/blog/design-matters/2020/design-is-the-strategy

Vaananen, T. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/blog/design-matters/2022/products-deliver-outputs-services-deliver-outcomes

The CNIO role is often seen as a link between nurses working clinically and the IT department, but in my case it also involves being a link between two recently merged trusts covering acute and community services.

The CNIO role is often seen as a link between nurses working clinically and the IT department, but in my case it also involves being a link between two recently merged trusts covering acute and community services. It’s fair to say I’ve had a varied nursing career. I qualified in 1994 and have held clinical roles and management ones. I started taking an interest in digitally-supported healthcare over 10 years ago when I discovered a love for data and how it can drive improvements for patients and staff.

It’s fair to say I’ve had a varied nursing career. I qualified in 1994 and have held clinical roles and management ones. I started taking an interest in digitally-supported healthcare over 10 years ago when I discovered a love for data and how it can drive improvements for patients and staff.

Burnout is defined as the result of “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” – and, as such, is a clear risk for NHS staff.

Burnout is defined as the result of “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” – and, as such, is a clear risk for NHS staff.